The Human Eye

The best visual tool that man has known for most of time is the human eye. It is the primary tool used by our brain to perceive the world and make sense it of it. While the basics of the human eye are explainable by optics, it is how that raw stimulus invokes imagery in our brain is what confused and fascinated people for a long time. It was in the late 1950s that two professors David Hubel and Torsten Wiesel, who were experimenting by inserting electrodes in the visual cortex of a cat and observing individual neurons[more].

They discovered that each neuron was tuned to observe only one kind of stimulus (say a straight vertical line) and only moving (or stationary) in one direction. Further they observed that the firing of neurons change as the orientation of the stimuli was changed. This understanding of each neuron as looking out for different stimuli in different orientations was later used in building convolutional neural networks.

Convolution : the function

Before anything else, one needs to understand why this function is used in the neural networks. To bridge that gulf of understanding, one first needs to realise that processing in the brain is mostly hierarchical. As mentioned above, we see that the visual cortex has a bunch of neurons which are tuned to detect very specific stimuli. But, how do these outputs make sense, i.e. say how can two neurons detecting a horizontal and vertical line, combine their observations to show the presence of a curved one? The answer lies in the hierarchical organization. Initially the V1 gets all the activations from the neurons detecting their stimuli, then these are sent to a different set of neurons in the same cortex to detect higher level features. Basically, the information captured by the first ‘layer’ of neurons is passed to the next ‘layer’ for detecting more complex features, one of which could be curves.

Ok, so the various activations of one layer of neurons is passed to another but how does the convolution function figure into all of this? Well, to detect the higher level features, the lower level features are convoluted to produce the activations in the next layer. Mathematically, a convolution function is applied to two functions to capture how the shape of one modifies the other. Put simply, imagine sliding the graph of one function over the other to ‘combine’ their outputs (watch gif).

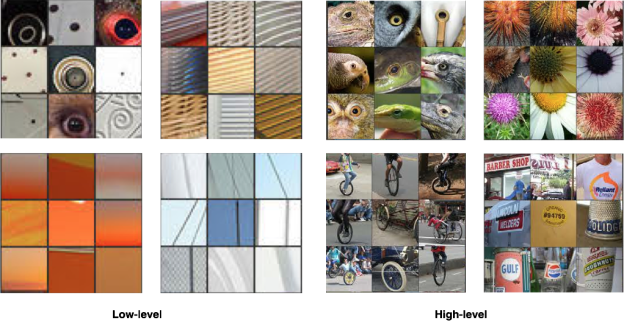

While it might seem quite simple, convolutions over a few layers allows the neural network (in your brain or your model) to observe really high level features such as a ball, or a beak, or even an eye.

The fall and rise of neural networks

Now that we have a rudimentary understanding of visual processing in the brain, let us move onto how things are generally processed in the brain. I am talking about neural networks of course. In the late 70s, when some connectionist models began underperforming, there was a growing restlessness in the AI community. Aided by lack of available data, low computational power and declining funding, an AI winter began. Neural networks became cool again in the 2000s, due to the internet and the onset of the information age. Powered by huge, open datasets and GPUs (Graphical Processing Units) the neural networks started performing, and sometimes outperforming humans. What makes these networks so powerful?

At the core of it, they still contain the perceptron used extensively in the connectionist models earlier. It is a mathematical model of a human neuron, i.e. it takes some input(stimuli), performs a simple computation and returns an output(activation). In modern neural networks, multiple perceptrons comprise of a single layer of the network, and multiple layers form the network (similar to what we saw in the visual cortex). This is a very high level understanding of the structure of a neural network, to learn more about the working of a feed-forward neural networks check out this video.

Now that we know how the neural network processes information it should be simple to just feed in images as input, the network passes it through the layers and we should get some meaningful output, right?

Putting it together

Not quite. Just like your ikea desk, it’s all there but it doesn’t quite seem to fit together. People came to the previous conclusion quite a few years back, but they were unable to create useful neural networks for visual tasks. There are two main reasons for it:

- Image data is basically pixel information. For smaller images, the input layer would be a few hundred values that get convolved over a few hundred more neurons in the next layer. But when we do the same with larger images, we see that the scale of computation keeps increasing and beyond a point becomes impractical.

- The layers beyond the input capture different stimuli which cannot be generalized across layers. This leads to loss of useful information, and retention of redundant information.

Well, so we can do simple visual tasks but for more general, complex tasks these networks were too inefficient to be used in practice. The call for a better method was answered by Yann LeCun and his team of researchers when in 1989, while working in the AT&T labs, they invented and applied a convolutional neural network to a handwritten digit recognition task. They came up with the idea that instead of having the n-number of weights(nodes in the layers after the input layer) process images fully, they would only go over slices of the images and detect each feature in those slices. Basically, imagine if each weight were a small window, and the network looks at the image through the window, sliding it over the whole of it to detect all the features it can. Not only does it drastically reduce the computation requirements, but it also makes the weights generalizable (i.e. once a feature is learned it can be applied to the same image in a different location and also in different images).

These weights are often called filters, or the receptive field. Each layer of filters captures a higher-level of information, similar to the visual cortex. So one can see how we drew inspiration from the human visual processing system to come up with convolutional neural networks to improve performance and accuracy of computer vision tasks.

To know a bit more about the nitty-gritties of CNNs you can check out the notes from Andrej Karpathy’s CS231n here. You can also play around with a sample network here.

Conclusion

In the beginning we saw how the human eye worked with the brain to provide use with a stream of visual information. From detecting dots and lines by the simple cells in the earlier layers to higher level features in the later layers, the mechanism was replicated in neural networks. The method was fine-tuned later by using layers of sliding, generalizable filters instead of fully connected layers. While this gives the reader a general overlook into the workings of convolutional neural networks, there’s many finer details that cannot be talked about without going deeper into the topic. Also, the architecture of the network discussed here is a very general one used for classification tasks. There are more creative approaches for different tasks such as object detection and neural style transfer(transferring an art style onto another image). I hope to cover the implementation of a convolutional neural network in the coming weeks where some of the aforementioned finer details will be discussed.

References: